Blueberries go from B.C. to Taiwan, and back

If someone had told Fred Liu 10 years ago that he would become a blueberry farmer in his new home in Metro Vancouver, he would have dismissed it as nonsense.

“I was an IT guy, trained to work with stock-market software and data systems,” said Liu, the founder and owner of Richmond-based Lohas Farm. “I was a total outsider to this. But the first time I tried a fresh blueberry, it was a revelation — so fresh, completely different from the ones stocked in the markets. So I ordered some for my friends back home.”

Liu, his wife and two children immigrated to Canada from Taiwan in 2005. He volunteered to help a friend pick blueberries at a farm in Maple Ridge in 2006 — and hasn’t looked back since.

Blueberries are rare in most parts of Asia, and Liu thought little about the business prospects of the fruit beyond a small amount of orders for family and friends. That first shipment of 1,200 pounds, however, quickly spread the word for B.C. blueberries across the Pacific. Orders grew to 6,000 pounds within two years, and Liu formed Lohas, renting farmland from Lower Mainland farmers and growing organic blueberries for the Asian market.

The culmination of the effort — an enzyme drink brewed from B.C. blueberries exported to Taiwan — has been such a hit in a limited release in Asia that Liu is now bringing the product back to Vancouver for sale, making an interesting case study of a B.C. agricultural product, in its trade journey, crossing the Pacific (twice).

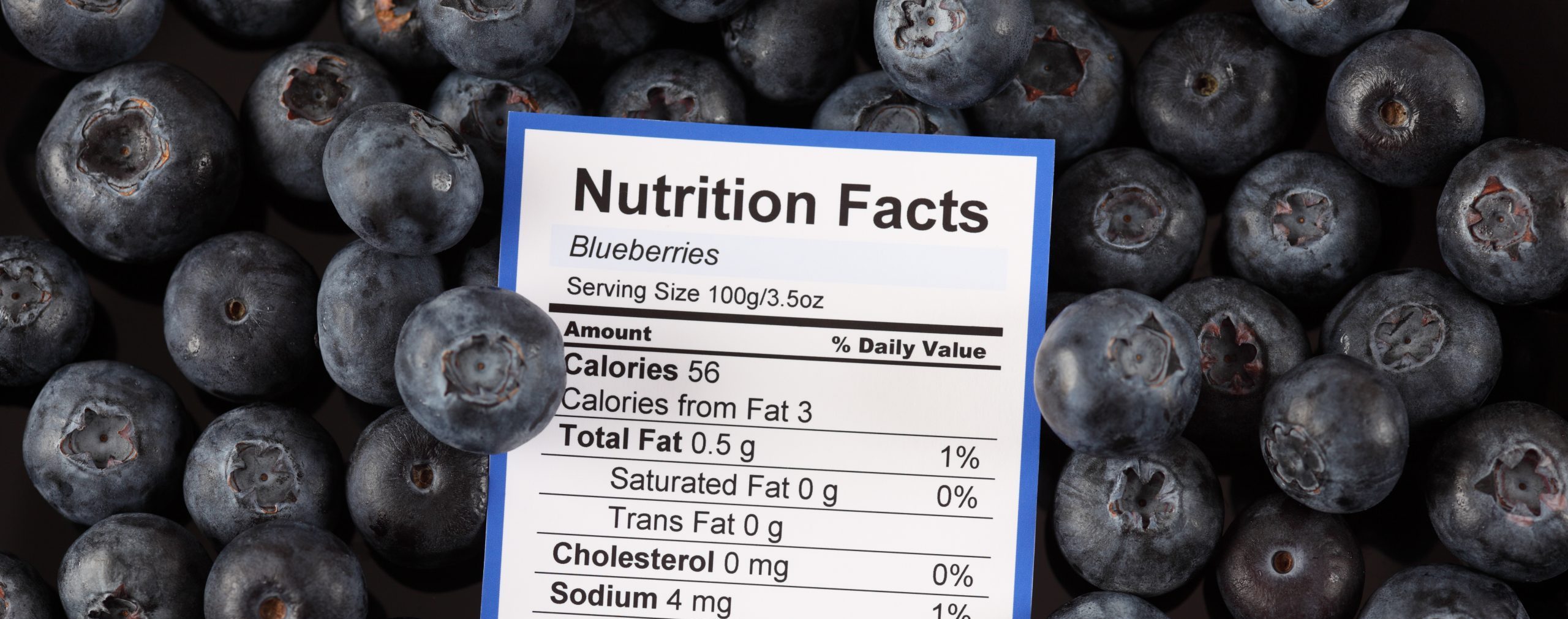

Health consciousness throughout East Asia has been rapidly rising in recent years, as improved living conditions and income levels coincided with increased pursuit of more sophisticated, healthier diets. Add to that a series of scandals hitting major domestic food producers, and many in Asia are turning to international fruits — such as B.C. blueberries.

Lohas is a small family operation, producing about 30,000 pounds of blueberries for export per year on about 10 acres of land. But the short harvest season (usually from July to August) means Liu faced a challenge of stocking Asian market shelves — where consumers expect products to be available year-round — with something that doesn’t have a long shelf life.

“In 2012, we were starting to produce a lot of blueberries, and you have to think about different ways for the products to reach consumers,” Liu said.

He partnered with Taiwanese Buddhist health-food producer Leezen to produce an enzyme drink made from blueberries. “I was on a business trip with my son to Guangzhou and Shenzhen in 2012, and we found some fruit-enzyme drinks were priced as high as CNY4,000 ($816) a bottle, higher than premium wine in some cases.”

Enzyme drinks are essentially juices of fruits fermented then bottled. The trend started in Japan and quickly spread throughout Asia, due partly to the product’s longer shelf-life, as well as supposed dietary benefits such as being high in antioxidants and potentially helping digestion. (University of Illinois researchers said in a 2012 report the drink contains bioactive compounds that are effective in suppressing blood-sugar levels, thereby reducing the risk of diabetes.)

Lohas first tested the enzyme drinks in a very small initial batch in 2013. Despite the limited, almost boutique-level micro-production, Lohas sold about 3,000 bottles of the blueberry enzyme drinks in Asia, mostly through direct online sales (although some store shelf presence was achieved in the Mainland Chinese market).

“Thank goodness we only had limited sales avenues,” Liu said. “If we marketed this at all, we would have ran out of stock almost immediately.”

Liu said Lohas just shipped this year’s batch of blueberries destined to become enzyme drinks to Taiwan last month. The plan is to produce 12,000 bottles this time. That was also when Liu thought the product — made from B.C. blueberries exported to the Taiwanese market for manufacturing — should be introduced back in Canada, where the whole process started. The choice made sense because there is little competition in the enzyme drinks market in Canada, Liu said, but the large number of Asian-Canadians should ensure a healthy business domestically.

Currently, consumers can only buy Lohas’s blueberry enzyme drinks directly at the farm, although more outlet options are being considered. Liu added that further expansion may be in the works for markets like Toronto, but Vancouver is the first step.

Liu stressed that Lohas’s blueberries are organic: No pesticides or chemical fertilizers, and fitting all Canadian regulatory requirements. Without it, the blueberries would lose their biggest selling point in Asian markets: The pristine “Organic fruit from Canada” brand.

“People’s image of Canadian blueberries in Asia is very, very good,” he said. “Vendors always say our blueberries look and taste much better than the ones you see from the United States, New Zealand or Argentina.”

“However, it’s going to take time for the drink to reach the mainstream market in Canada, because it’s a very new product. But Canada is an immigrant country. There’s lots of interaction between cultures, and people accept and celebrate differences. So I think it will be well-received.”

10/13/2015

Photo: Fred Liu of Lohas Blueberry Farm with blueberry drink Richmond, BC. October 8, 2015. Canadian family develops drink made from BC blueberries, which gains popularity rapidly in Asia. The product is now being marketed back in Canada.By Arlen Redekop , Vancouver Sun

Source: The Vancouver Sun