100 years of building a better blueberry

Life is just a bowl of cherries, but where would we be without the blueberry?

It fills pies that shout “summertime,” transforms pancakes, brightens cereal, glorifies vanilla ice cream, and perfects the muffin.

So you might think that fat, sweet blueberries have been around, like sunshine, forever. But no.

Nature gave us instead the small “swamp huckleberry,” as the wild blueberry was once known in these parts.

It took Elizabeth White, a visionary young farmer from Burlington County, working with an inspired botanist, to launch the modern blueberry industry 100 years ago.

Now worth $850 million annually, the industry literally traces its roots to the Pinelands.

The California-based U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council is this year marking the centennial of the berry’s commercial introduction and will hold its annual convention in Philadelphia in October so that members can travel to Pemberton Township to see where it all began.

“She was the oldest daughter of Joseph J. White, a Quaker cranberry grower,” Albertine Senske explained on a recent overcast afternoon.

Senske, 79, was sitting in a large clapboard house off Whites Bogs Road where a framed portrait of Elizabeth White gazed from over the fireplace. Outside, scrub pines coated with silver-green lichen shuddered in the wind.

Plain to the point of spare, this is Elizabeth White’s former home, part of a complex of buildings, fields, and bogs called Whitesbog Village in Brendan T. Byrne State Forest.

On April 2, the Whitesbog Preservation Trust will conduct a daylong symposium (whitesbog.org) on the local history of the highbush blueberry and White’s contribution to it. Born in 1871 in nearby New Lisbon, she died in 1954.

Never married, “she helped her father run the business,” explained Senske, Whitesbog’s archivist, “and they were always looking for a second crop that might cushion them in summer” if the cranberry harvest performed badly in fall.

Alas, little else but cranberry grew well in the sandy soil of South Jersey’s pine forests – the reason colonial farmers had derisively dubbed this region “the barrens.”

That changed in 1910 when White one day spotted an article, “Experiments in Blueberry Culture,” in a U.S. Department of Agriculture bulletin.

“Elizabeth says to her father, ‘Ha, ha. Let’s find out what this fellow’s got to say,’ ” Penske, a former Philadelphia schoolteacher and systems analyst, recounted.

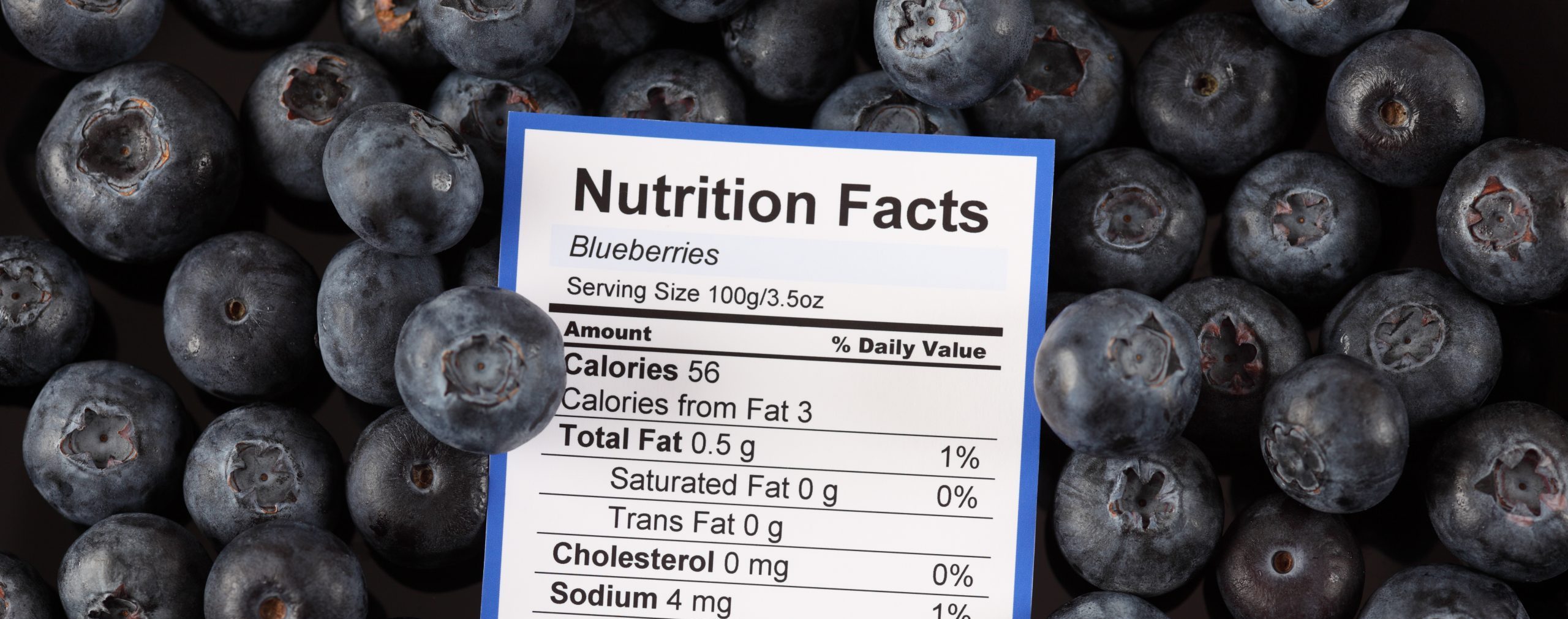

The article’s author, USDA botanist Frederick V. Coville, had discovered that blueberry bushes needed highly acidic soil, and must be cross-pollinated, because they don’t self-pollinate – two of several reasons why they usually failed as planted crops.

Coville reported, however, that he had been able to cross a few wild “lowbush” and “highbush” varieties at a farm in New Hampshire, and was planning further experiments.

“I’d like to get in the middle of all this,” White wrote him, noting that wild blueberries grew in abundance on her family’s 3,000 acres. (Cranberries and blueberries belong to the genus vaccinium, and need wet, acidic soil.)

She invited him to do research on the White farm, and Coville agreed. The two would go on to form a partnership that has become legendary in modern U.S. horticulture.

“Coville arrives on March 1, 1911,” said Senske, “and explains he will need some ‘raw materials’ – wild blueberry bushes – with which to work.

“Well, the people who knew where the best bushes were were the local woodsmen,” who sold wild berries to local hotels. “And the person who knew the woodsmen was Elizabeth.”

One of those was a local named Ezekiel Sooy, who for a fee led Coville and White to his best bushes. Coville selected three and shipped them to his greenhouse laboratory in Washington, and White began the search for more.

The next year, she started handing out glass canning jars bearing an inch of formaldehyde, along with a ring gauge for measuring berry diameters. She instructed her woodsmen to pick from their best bushes, drop samples in the jars, and note which came from which bush.

“She paid them by size, and if she and Dr. Coville liked what they saw, she would say to the woodsman, ‘I’d like to buy your bush,’ and he’d lead her to it,” Senske said.

“She’d tag it and in November, when the sap had gone back into the bushes, she’d dig them up, bring them back here, and winter them.”

White planted 100.

Out of the 100 she recommended six to Coville for hybridization, naming each after the locals who had discovered them in the wild. The “Dunphy” got its name from 10-year-old Theodore Dunphy, and the “Rubel” – still available at nurseries – for Ruben Leek, a Chatsworth carpenter.

In 1915, Coville sent White cultivars he’d created at his greenhouses in Washington, and in 1916 White harvested the very first commercial crop of hybridized “highbush” blueberries.

“She sold the entire crop – 17 crates of 32 pints each – to the Hudson River Day Liner,” a ferry service, said Senske. “She made $114.82 the first year.”

Within a decade, blueberries were developing into major commercial crops, and are today grown in 13 states, Canada, and Chile. California leads nationally in productivity, with $106 million worth of fruit grown in 2014. New Jersey is fifth, with nearly $80 million.

A century later, Coville’s and White’s research methods continue in South Jersey.

“I describe myself as a blueberry breeder,” said Mark Ehlenfeldt, a research geneticist for the USDA, “and what we’re most concerned about here is turning out new blueberry varieties.”

Ehlenfeldt, 59, wearing a straw hat, was standing in one of the sheet-plastic greenhouses that dot the Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research outside Chatsworth.

“One of the things going on in the industry is a move toward more mechanical harvesters,” he said. “So for that you need a certain kind of blueberry: firm, and one that ripens more or less at the same time.”

Spread before him were dozens of black plastic flats containing russet-green seedlings one inch high. “This is a variety from North Carolina with very, very firm fruit,” he said, pointing to a cluster of flats labeled “Reveille.”

Its firmness made it ideal for mechanical harvesting, Ehlenfeldt explained, but he was crossing it with varieties like “Midcrop” and the late-season “Elliott” for better flavor and different growing times.

Taking a tiny white flower bud between his fingers, Ehlenfeldt shook a bit of pale yellow pollen onto his thumbnail, then dabbed it onto the stigma – a little green filament – of another.

“It will take a month and a half for that fruit to develop. Then we harvest it off the plant, extract the seed, and plant it in October. That’s the starting point for the next generation.”

They will grow for three years before he and his team will know what kind of fruit each crossing has produced.

Photo: USDA researcher Mark Ehlenfeldt – he calls himself a “blueberry breeder” – checks hybrids at the research center, where the aim is find to new varieties. MARK C. PSORAS

The Philadelphia Inquirer

http://www.philly.com

03/27/2016