Yahoo! Profiles the “Blueberry Queen”

Elizabeth White, a true pioneer for the industry, is appropriately also known as the Blueberry Queen. Building the foundation for the  commercialization of highbush blueberries was no easy task over 100 years ago, and to this day, her recognition reaches way beyond the agricultural industry.

commercialization of highbush blueberries was no easy task over 100 years ago, and to this day, her recognition reaches way beyond the agricultural industry.

With the help of the Council’s own promotions, her story has been picked up and told in local and national outlets reaching millions of consumers. The reach of those stories just spread exponentially with a recent profile story on Yahoo! News, detailing the origins of the blueberry industry and Elizabeth White’s work with the USDA.

Yahoo! reaches a wide-ranging consumer audience across the world, with over 86 million individual visitors to its website. With a good chunk of our target audience having interest in their foods’ origins, our expectation is that readers learning the history of the highbush blueberry will in turn be more inclined to buy and enjoy blueberries for years to come.

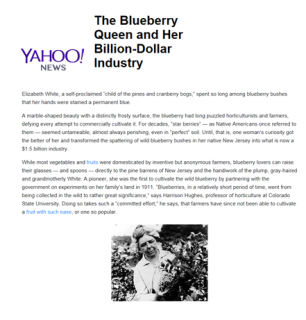

The Blueberry Queen and Her Billion-Dollar Industry

Elizabeth White, a self-proclaimed “child of the pines and cranberry bogs,” spent so long among blueberry bushes that her hands were stained a permanent blue.

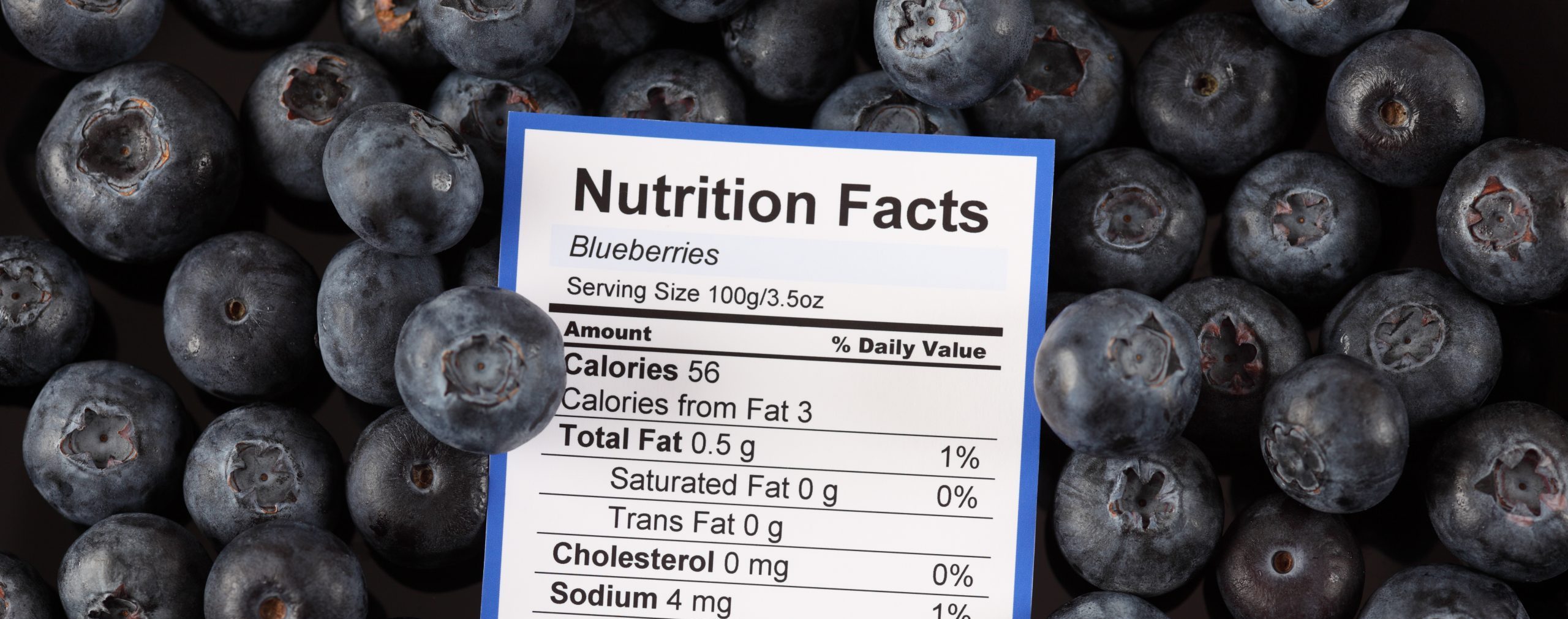

A marble-shaped beauty with a distinctly frosty surface, the blueberry had long puzzled horticulturists and farmers, defying every attempt to commercially cultivate it. For decades, “star berries” — as Native Americans once referred to them — seemed untameable, almost always perishing, even in “perfect” soil. Until, that is, one woman’s curiosity got the better of her and transformed the spattering of wild blueberry bushes in her native New Jersey into what is now a $1.5 billion industry.

While most vegetables and fruits were domesticated by inventive but anonymous farmers, blueberry lovers can raise their glasses — and spoons — directly to the pine barrens of New Jersey and the handiwork of the plump, gray-haired and grandmotherly White. A pioneer, she was the first to cultivate the wild blueberry by partnering with the government on experiments on her family’s land in 1911. “Blueberries, in a relatively short period of time, went from being collected in the wild to rather great significance,” says Harrison Hughes, professor of horticulture at Colorado State University. Doing so takes such a “committed effort,” he says, that farmers have since not been able to cultivate a fruit with such ease, or one so popular.

The eldest daughter of landowner Joseph J. White, aka “the Cranberry King,” so called for his extensive fruit holdings in the Garden State’s agricultural village of Whitesbog, White spent her younger years close to her father’s side, immersing herself in farming methods and agricultural research. “I always shirked the woman’s job of serving meals, eager to hear all the cranberry talk,” she reportedly told a meeting of the Cranberry Growers Association in 1942. But the culmination of years of research came at the age of 39, in 1910, when White stumbled across a report about blueberries from the U.S. Department of Agriculture by a botanist named Frederick Coville.

The eldest daughter of landowner Joseph J. White, aka “the Cranberry King,” so called for his extensive fruit holdings in the Garden State’s agricultural village of Whitesbog, White spent her younger years close to her father’s side, immersing herself in farming methods and agricultural research. “I always shirked the woman’s job of serving meals, eager to hear all the cranberry talk,” she reportedly told a meeting of the Cranberry Growers Association in 1942. But the culmination of years of research came at the age of 39, in 1910, when White stumbled across a report about blueberries from the U.S. Department of Agriculture by a botanist named Frederick Coville.

Coville had figured out why wild blueberries would not grow when people tried to domesticate them in their home gardens, advising that the fruit needed acidic soils, unlike most food crops. Inspired, White sent the USDA a letter inviting them to use her father’s land, where the soil was suitably acidic, to test the hard-to-tame fruit, and within months Coville was working with her. White even recruited locals, so-called “pine people” from the Pine Barrens area, to collect bushes, noting on flyers, “I will pay for huckleberry bushes, when the largest berries on it will not drop through holes the size of the blue dots.”

The cultivation became a massive research undertaking, digging up selected bushes, bringing them back to Whitesbog, where cuttings were taken and rooted. The most promising — in all taken from about 100 bushes — were then sent to Washington, D.C., where Coville would hybridize them in government greenhouses. White, who had great respect for the men involved in the work, named each bush for the person who found it: Harding, Hanes, Sam and Rubel — the latter was for a man named Rube Leek, but White didn’t think “Leek” was a blueberry name, and “Rube” was not appropriate “for so aristocratic a bush,” she said, so they settled on “Rubel.”

When the resulting seedlings were a year old, they were sent back to Elizabeth’s trial fields at Whitesbog. So how were the workers inspired to keep trying? “The fruit is very tasty, and that’s what gave the motivation,” says Nicholi Vorsa, director at the Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry and Cranberry Research and Extension at Rutgers University, which continues White’s work to this day. “When you have to go tromping through the woods and swamps to get your blueberries, your efficiency is not great, and it’s hit and miss.” But the thought of being able to grow the berries at will spurred them to action. By 1916, White and Corville had cultivated their first commercially grown blueberries, and about 600 quarts of blueberries were shipped from the fields at Whitesbog. “That was my special work,” White wrote in a gardening journal article called “Taming Blueberries,” referring to the five-year period of breeding and domestication. Twenty years later, 600,000 quarts of berries were developed at Whitesbog. Blueberry production is expected to surpass 1.4 billion pounds this year, according to the U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council.

Unlike today, with farmers worried by insects and plant afflictions, the biggest risk came from birds, who, she wrote, “think God made blueberries especially for them.” Yet White’s legacy for inventiveness lives on in what has become an American cultural icon — the blueberry-flavored Jelly Belly, created for Ronald Reagan’s presidential inauguration in 1981. Today there are over 100 different varieties of the fruit, but thanks to fifth-generation blueberry farmer Joseph Darlington, who planted the blueberries in the same spot as his great aunt, only one variety carries the name of the true blueberry queen: Elizabeth.

Photo: Elizabeth White was the first to tame wild blueberries. Source U.S. Department of Agriculture