Taste testing helps UF scientists grow better Florida blueberries

When the words “genetics” and “food” are combined, flashes of mad scientist-esque test tubes or mutant carrots may come to mind.

But the research plant breeders conduct at University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) helps make the foods we eat more digestible for growers and consumers.

“Most of the produce or crops that we use today, they have been improved or they have been, you know, developed first by a plant breeder,” said Dr. Patricio Muñoz .

Muñoz has been a plant breeder for the better part of 17 years.

Plant breeders work in fields and labs to discover the right genetic combination of a particular crop. That research later informs farmers about what plant varieties are best to grow.

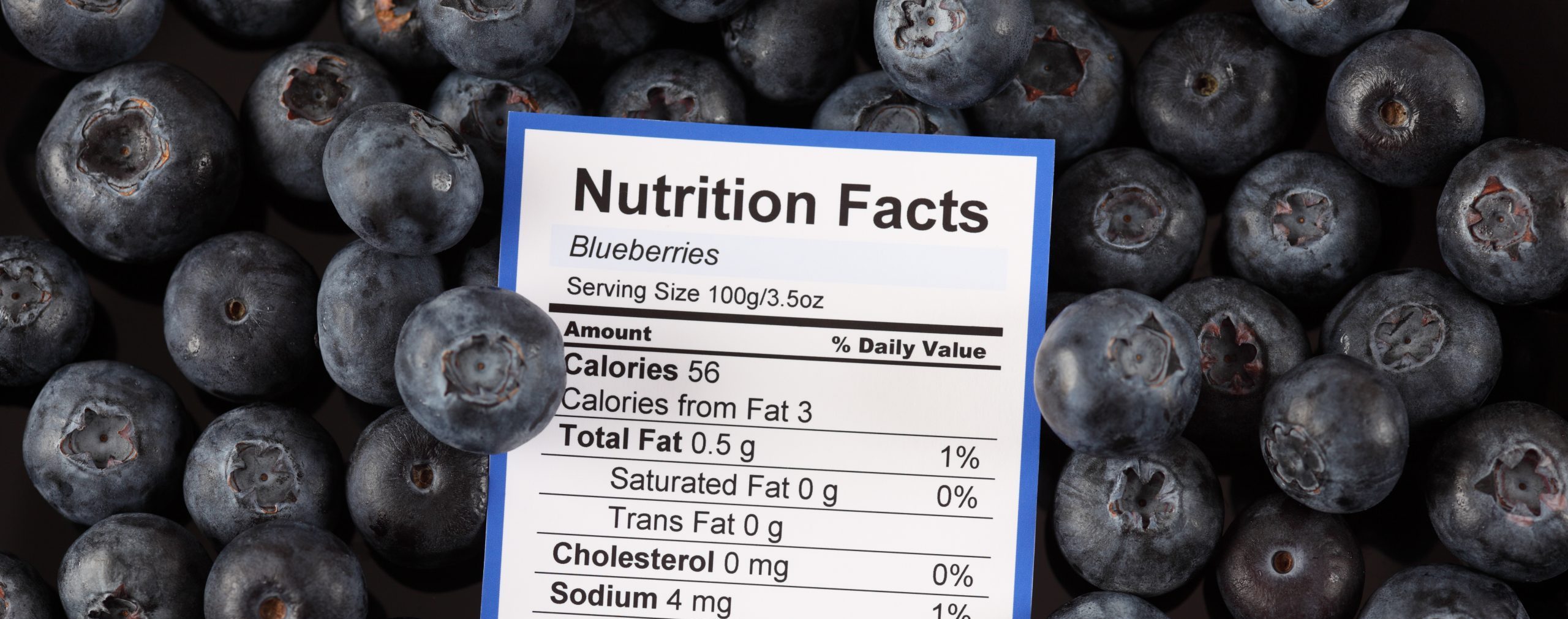

Muñoz and his team at the University of Florida have been breeding Florida blueberries that not only taste good, but better ward off pests and are more resilient to changing climate conditions, such as heat. More recently, he has been analyzing how aroma impacts the flavor of blueberries.

“Plant breeders, or blueberry breeders, have been noticing that some fruits have these aromas, and some others [do] not. The question that we have all the time was like, does this matter to the consumers,” Muñoz said.

Dr. Charles Sims, UF/IFAS professor of food science and human nutrition, helped Muñoz and his team assemble consumer taste-testing panels to find the answer to their question. He explains that while blueberries don’t traditionally have a smell, it’s the act of biting into the fruit that releases taste.

“That blueberry taste, per say, is not really a taste. It’s really a smell that we’re detecting from the mouth, and that’s what we generally call flavor. So, we would distinguish flavor and taste as two separate things, but a consumer would just intermix those together probably,” Sims said.

Taste testers in this study were given a set of aromatic blueberries and non-aromatic blueberries and asked questions about the varieties’ appearance, color, texture, and flavor. Dr. Muñoz says that after two years of running these panels, testers chose the aromatic variety more often, and that comes down to the fruit’s genetics.

“We were able to point pinpoint a few and naturally occurring chemicals called terpenes that actually are associated with this aromaticity,” Muñoz said.

“And in the genetic part, [we] to try to find out what are the genes that actually are involved in the regulation of this terpene. So then, with the idea that in the future, we can do the selection for those specific genes more heavily and then deliver fruit that’s going to be more enjoyed by consumers.”

The feedback from taste testers helps Muñoz identify what characteristics consumers respond to in blueberries allowing him to better select what variety to release. Sims says this research benefits Florida blueberry growers.

“Hopefully, since they have good flavor and they can produce good yields, then these berries will sell well in the market, and we’ll improve the profitability or sales of Florida blueberries,” Sims said.

Muñoz says he always wanted to make a difference in the world, and in his specific case, that involves blueberries.

“We always get to innovate on what we are doing, and then sometimes, by just serendipity, we find characteristics that you didn’t even know existed. Then they become a novelty, and then they if they are good, for humanity. Sometimes they [blueberries] become something that is everywhere and that’s fascinating.”

01/09/2022